Sclerotinia sclerotiorum is a yield-limiting fungal plant pathogen, present on every crop-producing continent with over 500 known susceptible host plants, including weeds. In South Africa, hosts include (but are not limited to), cabbage, canola, cauliflower, drybean; hubbard squash, soybean, sunflower, pea and potato.

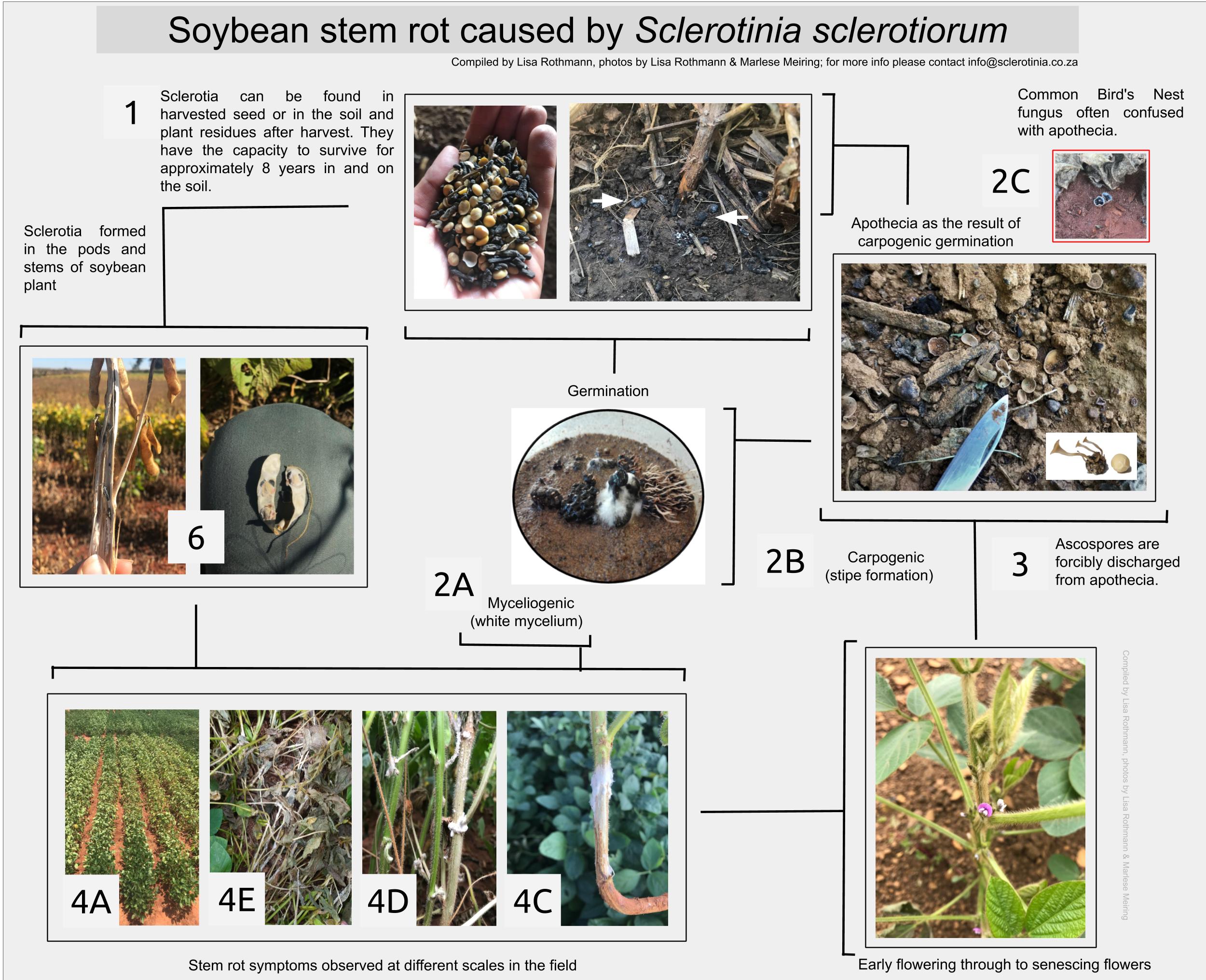

The diseases caused by S. sclerotiorum are characterised by the distinguishing features namely, watery soft rot (4A and 4B; symptoms), followed by white cottony mycelia (4C and 4D), a shredded appearance (4E) and ultimately melanised mycelium, known as sclerotia (5A, 5B, 6; signs). The sclerotia are crucial to the lifecycle of this pathogen, they are the survival structures and with the ability to survive for up to eight years in and on the soil (1). The complexity of this pathogen is complicated due to the sclerotia affording this pathogen the opportunity to form two inoculum types, mycelia (product of myceliogenic germination; 2A) and ascospores (product of carpogenic germination; 2B). These germination pathways are induced under contrasting environmental conditions. Carpogenic germination usually occurs under lower temperature ranges than that of myceliogenic germination, however, both pathways prefer high relative humidity, moisture or leaf wetness. The initiation of the stipes from sclerotia leads to the development of apothecia (3), a mushroom-like structure, which appears much like a teacups’ saucer. Ascospores, infection propagules, are forcibly discharged from apothecia when air pressure changes are observed within the canopy, widely dispersing spores. Apothecia are frequently misidentified as the common bird’s nest fungus (2C), belonging to the Nidulariaceae family. In contrast, mycelium of S. sclerotiorum is responsible for crown and stem infections nearer to the soil surface.

As a result of the wide host range, pathogen biology, and environmental dependence the management of Sclerotinia diseases requires an integrated approach. The complexity of managing Sclerotinia diseases are extenuated as no conventional resistance exists within any of the host crops. Management strategies have thus relied on reducing the opportunity for the sclerotia to germinate and thus keep the sclerotial population limited, as well as ensuring the disease initiation risk is limited. Planting dates, crop rotations, population densities, tillage practices, biological and chemical control have all provided limited (and at times inconsistent) control to Sclerotinia diseases.